Authors: Aaron GU丨Pengfei YOU丨Duzhiyun ZHENG丨Yuzhen ZHANG丨Fengqi YU[1]

In recent years, license-in/out transactions have become the most common way for innovative drugs and medical devices (including medical aesthetics) companies to collaboratively develop and commercialize medical products and related technologies. According to public information, in China, the total amount and number of investment and financing in life sciences sector have witnessed a significant decline from 2021 to 2023, with the investment amount being only a quarter of that in 2021. However, the upfront payment for business development (BD) transactions in life sciences sector has reached 5.045 billion US dollars in 2023, with a potential payment totaling up to 54.89 billion US dollars[2]. The scale of license-out transactions has been continuously expanding.

Our team has been 100% dedicated to the legal work in the life sciences field, and we are honored to have the privilege of assisting numerous multinational pharmaceutical and medical device companies, as well as leading innovative biotech companies in China, in conducting licensing transactions and research collaboration projects. Such collaborative projects involve various small molecule drugs, ADC drugs, RDC drugs, mRNA drugs, AI pharmaceutical technologies and products, cell therapy products such as CAR-T/CAR-NK/TIL, medical aesthetics products, various innovative medical devices for treatment or diagnosis (IVD/LDT), etc. Previously, we have analyzed the key terms of the license-in/out transaction projects from the perspective of regulatory compliance. (please refer to: Anatomy of Licensing Deals from China Regulatory Perspective).

At this very beginning of the new year, in order to enhance industry's understanding of the key terms of license-in/out projects and the noteworthy considerations between collaborating parties, we have reviewed over fifty licensing agreements (including co-development agreements) handled in the past two years. We have selected several key terms to compare these agreements horizontally with respect to seven aspects including marketing authorization applications, license grants, financial terms, intellectual property, diligence obligation, exclusivity, and termination terms. In this article, we would like to present our observations on the characteristics of licensing transactions in China in recent years, hoping to provide some reference for future transactions and developments in the industry[3].

Marketing authorization applications

The selection of the Market Authorization Holders of drugs or the registrants or record filing parties of medical devices (collectively referred to as "MAH") is crucial for future commercialization of the products and the allocation of responsibilities between the collaborating parties. We have found that, in the vast majority (85.2%) of the projects, the collaborating parties have explicitly stipulated in the licensing agreement who will be the MAH for licensed products. The rest 14.8% of the projects do not specify the MAH. Such projects share a common characteristic that they are all targeting products in early development stages such as pre-clinical research, and arrangements for the MAH of the final product therefore can be temporarily postponed. If these projects progress further, the parties will negotiate the selection of the MAH.

Among the projects with clear MAH arrangements, on one hand, all of the one-way licensing agreements specify that the licensee ("Licensee") shall be the MAH for the licensed products within licensed territory with the rights and responsibilities to submit and maintain all relevant regulatory filings in its own name. In some agreements, the Licensee's affiliates, sublicensees ("Sublicensee"), or mutually agreed third parties may also be chosen by the Licensee as the MAH. On the other hand, the allocation of MAH is more diverse in co-development projects.

Additionally, in approximately 7.4% of the projects, further arrangements regarding MAH have been made for the early termination of the project. Depending on different circumstances that result in the early termination, a transfer of the MAH may take place.

License grant

I. Sublicensing

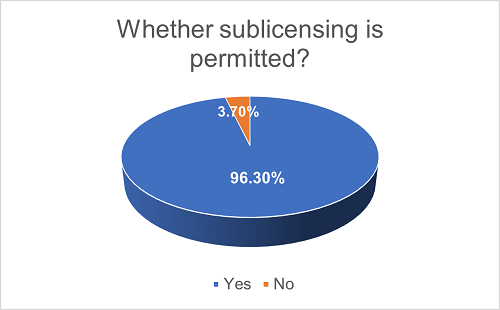

In the vast majority (96.3%) of the projects, the Licensee is granted the right to sublicense the licensed technology, while only 3.7% of projects do not permit sublicensing. Among the projects that allow sublicensing, 3.8% of them explicitly restrict the scope of Sublicensee, prohibiting the Licensee from sublicensing to any third party other than those Sublicensees listed in the agreements.

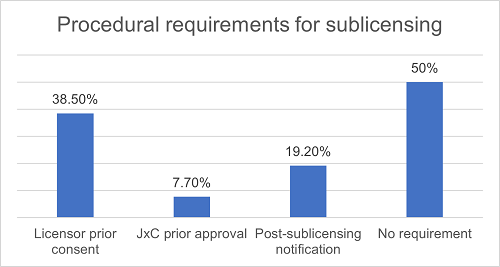

In order to supervise the Licensee's performance of its sublicensing rights, the licensor ("Licensor") may require that the grant of sublicenses must be subject to its prior approval, or the Licensee must provide timely notification and furnish copies of the sublicense agreements after granting sublicenses. We have found that in projects that permit sublicensing, approximately 38.5% of them require prior approval (usually in writing) from the Licensor, 19.2% of them require the Licensee to notify the Licensor and provide a copy of the sublicense agreement within a certain time period after sublicensing, 7.7% of them require the sublicensing to be approved by the joint project committee (JxC), and about 50% of them do not have procedural restrictions on sublicensing.

A considerable proportion (about 30.8%) of the projects have applied a combination of various procedural restrictions. For example, different requirements may be applied depending on the categories that Sublicensees belong to. Additionally, in a small portion of co-development projects, each cooperating party may be subject to different procedural requirements. This demonstrates that in practice, taking into account different collaboration backgrounds and business needs, there are flexibilities among the collaborating parties in arranging the conditions of the sublicensing right.

II. Grant-back license

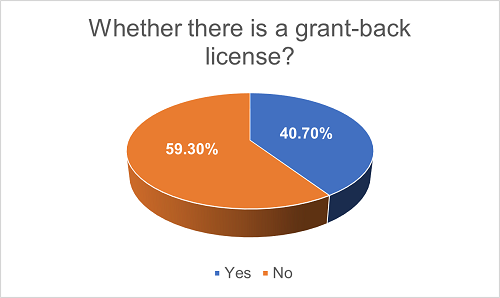

In practice, the Licensor may also require the Licensee to grant back a license with respect to the technology improvements generated by the Licensee, authorizing the Licensor to use such improvements outside the licensed territory or licensed field. However, we have found that projects with explicitly defined grant-back licenses do not yet represent the majority, accounting for only about 40.7%, while the remaining 59.3% do not have such provisions. We understand that this is related to the specific situations of the collaborating parties involved in each project and the nature of their business operations. Factors to be considered mainly include whether the Licensee is likely to generate valuable intellectual property in the project and whether the Licensor's future business operations will require the use of such intellectual property.

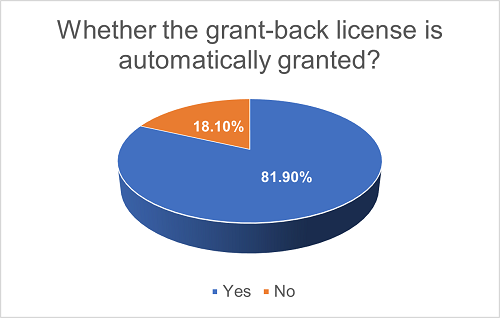

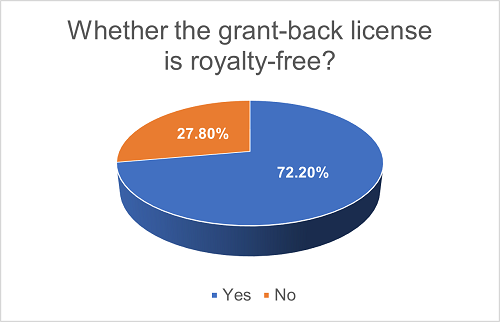

In projects with grant-back licenses, 18.1% of such licenses are not automatically granted; instead, what the Licensor owns is an option right to require the Licensee to grant the license in the future. The financial considerations and other conditions for such grant-back licenses may be separately agreed upon. Furthermore, in the majority (72.2%) of such projects, the grant-back licenses are royalty-free.

Financial terms

I. Milestone payment

Approximately 63.0% of agreements include provisions for milestone payments. We further analyzed some details of these provisions.

1. Automatic achievement of prior milestone events

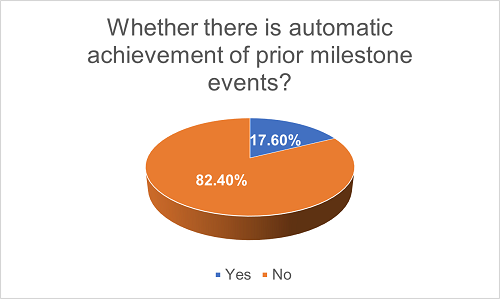

Under some licensing agreements, when a later milestone event is triggered, all prior milestone events are considered to be achieved automatically. As a result, the Licensee is required to pay the amount corresponding to the triggered milestone event as well as all prior milestone events. We have found that, among all agreements with milestone payment, only 17.6% of them have such arrangement. This indicates that this arrangement has not been widely adopted in practice.

2. Milestone events

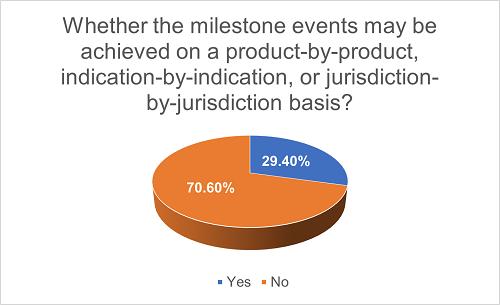

Sometimes, a licensing project may result in more than one licensed product, target more than one indication, and/or involve more than one jurisdiction. In such projects, the Licensor, in order to maximize economic benefit, may require the milestone events to be achieved on a product-by-product, indication-by-indication, jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction basis. As a result, a single milestone event may be triggered more than once, and accordingly, the Licensor may seek multiple milestone payments for each product, indication or jurisdiction. Among all projects with milestone payment agreements, we have found 29.4% of them have adopted such approach.

II. Royalty

Approximately 70.4% of the projects include provisions for royalties. We have conducted further analysis on the royalty terms, bases, and reductions of these projects.

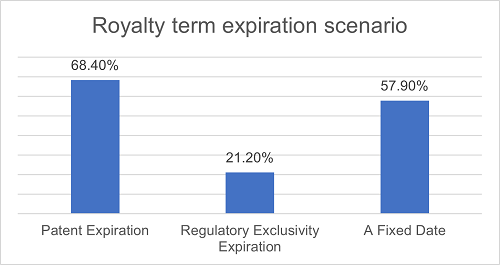

The royalty terms of almost all projects start from the first commercial sale of the licensed products, while the expiration date of such terms varies. About 68.4% of projects set the expiration date of the last-to-expire valid claim as one of the expiration events. 57.9% of projects set a fixed period as one of the expiration events. 21.2% of projects set the expiration date of all regulatory exclusivity as one of the expiration events. It is worth noting that 42.1% of the agreements have combined two or more triggering events mentioned above, with the expiration date being the earliest/latest occurrence among these events. There are also some agreements under which the obligation for the Licensee to pay royalties will remain valid for an extended period.

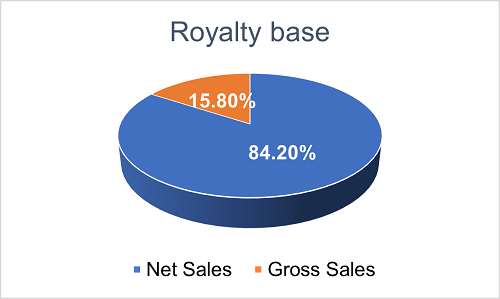

As to the royalty base, 84.2% of the projects use "net sales" as the base for royalty calculation, while the remaining 15.8% use "gross sales" instead. Choosing "net sales" as royalty base remains the predominant industrial practice. It is worth noting that each agreement may contain subtle yet impactful differences in the definition of "net sales".

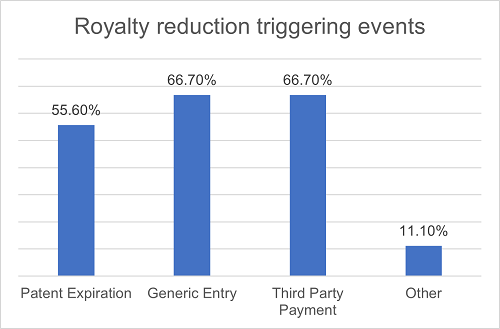

In terms of royalty reductions, nearly half of the projects outline specific conditions under which the royalties can be reduced. Common triggering events may include patent expiration, generic entry and third-party payment. Among all projects with royalty reductions, 55.6% of them attribute patent expiration as the reason for reduction, 66.7% cite generic entry as the triggering event (with nearly half of them further requiring that the entry of generic drugs must result in sales of the licensed products falling below a specific threshold), and 66.7% specify that certain third-party payments can be deducted from the royalty amount due and payable. 11.1% of the projects have also mentioned other triggering events, such as compulsory licenses or reductions because of the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act. Over half of all projects provide multiple reduction scenarios mentioned above.

III. Sublicense income

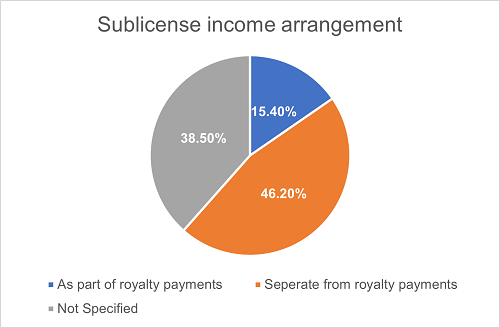

In license-in/out transactions permitting sublicensing, the allocation of sublicense income provides another essential avenue for the Licensors to gain economic interests. Typically, the Licensors may seek sublicense income by either including such income in the royalty base or by separately obtaining a share from the sublicense income.

We have found that around 15.4% of the projects permitting sublicensing have employed the former approach, while approximately 46.2% opt for the latter. In 38.5% of the projects, arrangements for sublicense income remain unspecified.

Intellectual property

I. Ownership of Project IP

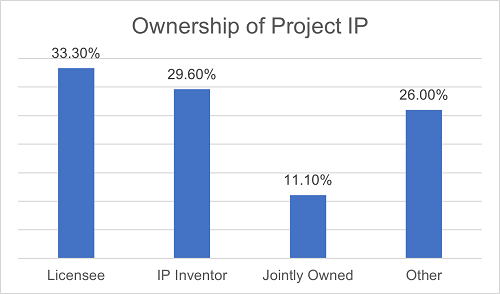

With respect to the ownership of project intellectual properties ("Project IP"), around 33.3% of the projects specify exclusive ownership by the Licensee, constituting the most common arrangement. Approximately 29.6% of the projects provide that the Project IP shall be owned by the inventor. If such Project IP is jointly invented, it shall be jointly owned by both collaborating parties. Under 11.1% of the agreements, the Project IP is jointly owned by both parties. The remaining agreements provide other allocation rules, such as determining the ownership based on the specific content or type of the Project IP. Such flexible arrangements are more common in co-development projects.

II. Responsible party for IP enforcement

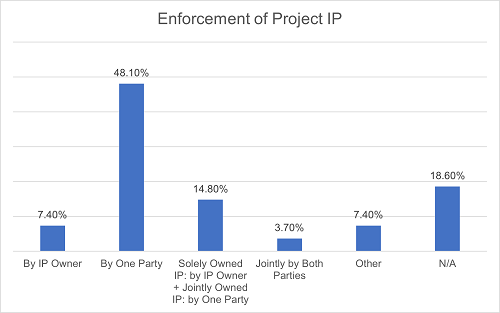

Firstly, regarding the licensed intellectual properties, 59.2% of all projects specify that the Licensor shall be responsible for the enforcement, 25.9% provide that the Licensee shall hold such responsibility, while the remaining 14.9% do not explicitly define the responsible party.

Secondly, regarding the Project IP, the scenarios are more varied and decentralized. 48.1% of the projects provide that the enforcement of all Project IP is solely the responsibility of one party. Under 14.8% of the agreements, each party is responsible for its solely owned Project IP while the enforcement of jointly owned Project IP is responsible by one of the parties. 7.4% of the projects provide that each party shall merely be responsible for the enforcement of the Project IP owned by itself. 3.7% of the projects state that both parties shall jointly enforce the Project IP. Additionally, 7.4% of the projects opt for alternative arrangements, such as assigning such responsibilities based on different territories controlled by different parties. The remaining 18.6% of the projects do not address this matter.

Diligence obligation

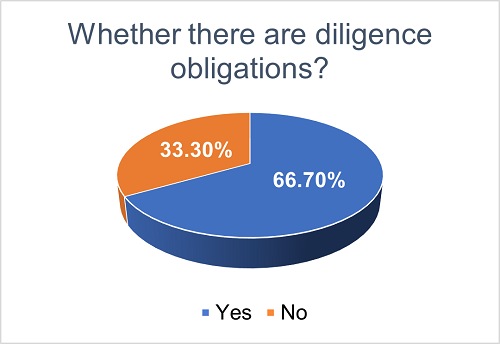

To facilitate the successful exploitation of the licensed products, licensing agreements may outline the diligence obligations of the Licensee in one-way licensing projects (or both parties in co-development projects) throughout the development and commercialization phases. Approximately 66.7% of all projects have set out diligence obligations, while the remaining 33.3% do not explicitly specify such obligations.

The diligence obligations may have various standards. For the majority of agreements, the "commercially reasonable efforts" standard applies. The remaining minority have employed the "diligent efforts" standard or the "best efforts" standard. Apart from these abstract standards, a few agreements also stipulate some objective standards. For instance, approximately 33.3% of agreements have established specific diligence milestone events, and around 5.5% of agreements require the Licensee to make minimum annual commercial payments to the Licensor.

Exclusivity

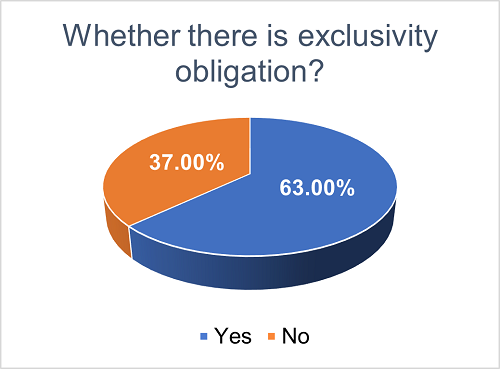

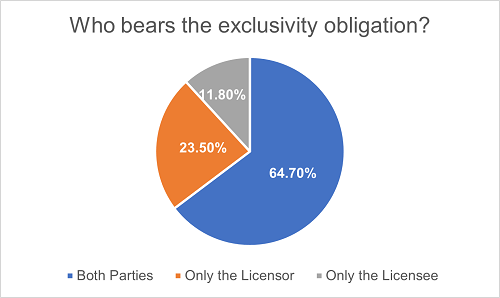

To ensure that the collaborating parties are both committed to advancing the development and commercialization of the licensed product, licensing agreements may outline non-compete obligations for each party. This helps to prevent detrimental effects on the interests of the other party. We found that approximately 63% of the agreements explicitly incorporate non-compete obligations, while the remaining 37% are silent on this matter.

Among the projects where the exclusivity obligation is explicitly stipulated, most of them (64.7%) provide mutual obligations for both cooperating parties. Under 23.5% of the agreements, only the Licensor bears the exclusivity obligation, while under the remaining 11.8% of the agreements, only the Licensee bears such obligation. The inclusion of non-compete obligations is closely related to the bargaining positions of each party, and it will significantly impact their future business endeavors.

Termination term

I. Unilateral termination right

Unilateral termination rights are common in license agreements. In most projects, both collaborating parties have unilateral termination rights, although there may be differences in the conditions for each party to exercise its rights. In a minority of projects, only the Licensor has unilateral termination rights.

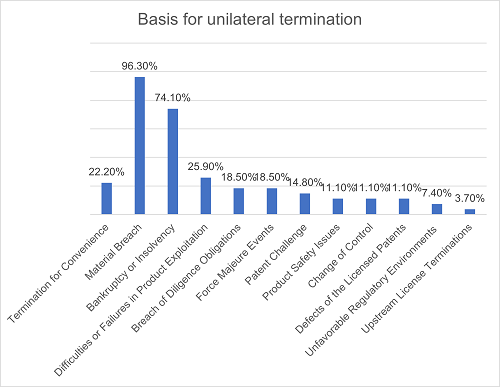

In terms of the triggering events for exercising unilateral termination rights, termination for material breach and termination for bankruptcy or insolvency are the most common, accounting for 96.3% and 74.1% respectively in all agreements. Generally, both the Licensor and the Licensee enjoy unilateral termination rights under these two scenarios. Other possible events include: difficulties or failures in the development or registration of the licensed products, the Licensee's breach of diligence obligations (such as failure to meet diligence milestones), force majeure events, patent challenge by the Licensee, product safety issues (such as SAE), a party's change of control, defects of the licensed patents (such as being rejected or invalid, infringing third-party intellectual property rights, etc.), unfavorable regulatory environments (such as trade controls), terminations of upstream licenses, etc. Additionally, in 22.2% of the agreements, one or both parties enjoy the right of termination for convenience.

II. Termination effect

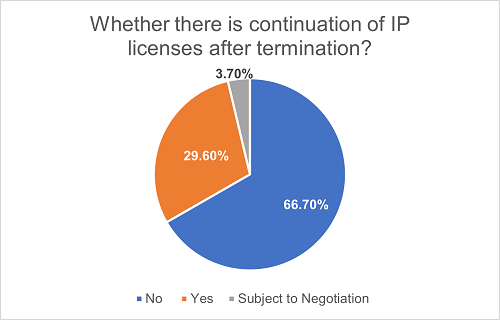

Typically, the license grant under a license agreement automatically terminates upon the agreement's termination or expiration. However, depending on the project's nature and the reasons for termination, some license agreements may also stipulate that the license may continue in part or in full after the termination or expiration of the agreement. We have found that 29.6% of the agreements have adopted this approach. Another 3.7% of the agreements specify that after termination or expiration of the agreement, the parties may otherwise negotiate the continuation of certain licenses.

Such arrangements are more common in co-development projects. Among all the projects where licenses remain partially or fully valid after the termination or expiration, 75% of them are co-development projects. This is mainly because, following the termination of such projects, one of the collaborating parties may intend to proceed with the development and commercialization activities independently or with a third party. As a result, they may still need the license from the other collaborating party to continue such activities.

In approximately half of the projects where the Licensee continues to get the licenses from the Licensor after the agreement's termination, such termination shall be due to the material breach or bankruptcy or insolvency of the Licensor. Moreover, the vast majority of such continuing licenses are royalty-free.

The preceding discussion provides a statistical summary of recent license-in/out projects handled by our team. While many agreements share similarities to some extent, there are also highly customized arrangements tailored to the specific backgrounds of different projects. When negotiating and drafting future licensing agreements, industry participants may bear in mind that other than adhering to common industry practices, they are never bound by any rigid rules. In order to promote friendly collaborations as well as protect one's own interests to the greatest extent possible, the parties may flexibly adjust the terms of the licensing agreements taking into account practical business needs and bargaining power of each party.

Important Announcement |

|

This Legal Commentary has been prepared for clients and professional associates of Han Kun Law Offices. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, no responsibility can be accepted for errors and omissions, however caused. The information contained in this publication should not be relied on as legal advice and should not be regarded as a substitute for detailed advice in individual cases. If you have any questions regarding this publication, please contact: |

|

Aaron GU Tel: +86 21 6080 0505 Email: aaron.gu@hankunlaw.com |

[1] Leyi Wang and Shuwen Sun have contributions to this article.

[2] MybioBD: The 2023 annual report on China's life sciences licensing BD transactions has been released with great significance, February 19, 2024, https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/DiSDuW48MGr1J5tpftQRew.

[3] This report is an important work product and copyright of Han Kun and should be treated as confidential information of the firm. No third party may copy, distribute, publish or reproduce this document, in whole or in part, unless with our written consent. The data presented in this article are all derived from licensing-related transaction projects in which the author has been involved in recent years. This report should not be relied on as legal advice or regarded as a substitute for detailed advice in individual cases. If you have any further questions or need professional legal services or support, please feel free to contact us.